Most trips to Belize follow a familiar arc. Time on the reef. A lodge near the jungle. A Maya site along the way. Many travelers leave believing they have seen the country.

What most never realize is that the southernmost district was still ahead of them.

Toledo lies at the far end of Belize, where the road narrows and the land grows quieter. Forest presses close to the highway. Rivers cross without warning. Villages appear briefly, then fall back into the trees. There are no arrival markers designed for visitors. You don’t ease into Toledo. You simply enter it.

That absence of spectacle has kept it off itineraries. It has also preserved exactly what travelers are starting to seek now.

A District Coming Into Focus

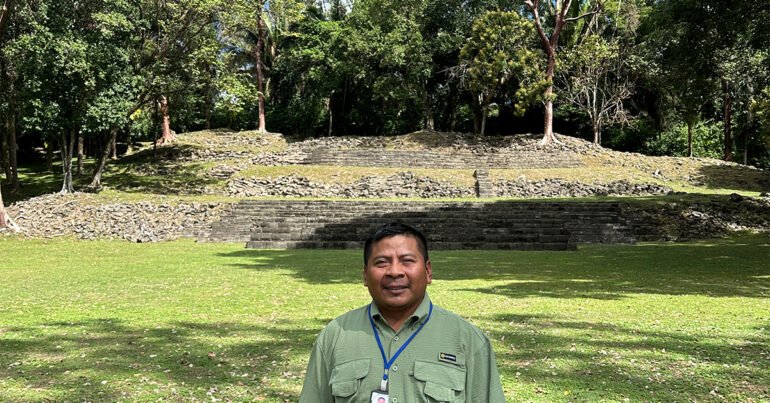

“Tourism is very important to Belize and to our communities,” says Jose Mai, a Maya community leader in the Toledo District. “It is one of the country’s main industries.”

Belize’s economy has long depended on tourism. Toledo’s relationship with it has been more gradual.

“Tourism here isn’t new,” Mai says, “but Toledo remains one of the least visited districts and one that is still developing within the tourism industry.”

That development is happening quietly. Small lodges open along rivers. Villages decide whether and how to host visitors. Travelers arrive not because Toledo has been promoted heavily, but because word now travels differently. People are looking beyond the familiar stops.

Toledo has not been waiting to be discovered. It has simply continued.

What Travelers Find When They Arrive

“Toledo District is very unique,” Mai says. “We have a lot to offer and a lot of natural resources.”

Those resources stretch across rainforest, rivers, caves, waterfalls, national parks, and Maya sites, but what defines Toledo is how closely all of it connects to daily life.

“We have caves, archaeological sites, national parks, and Maya living experiences,” he says.

Rainforest runs straight toward the Caribbean Sea. Rivers remain working waterways. Waterfalls sit beyond paths people already use. Maya sites remain closely tied to the communities that maintain them.

“We also have waterfalls and protected areas,” Mai says. “There are many different activities here.”

Nothing exists solely for visitors. That is what travelers notice first.

Culture Shared on Its Own Terms

“In Maya communities, cultural practices are very personal,” Mai explains. “Many people are hesitant to share them because their way of life is private, and that is understandable.”

Participation is selective. Not every village opens its doors. Not every household hosts. When it happens, the exchange remains direct.

“One of the things we are doing now is what we call the Maya Living Experience,” Mai says. “Visitors experience how we live, how we interact with the natural environment, and what nature means to us.”

Guests prepare food, eat together, and learn how everyday materials are used. Palm fibers become baskets. Seeds become art. The visit ends when the day ends.

“Our intention is to open our homes and share how we live, what we do, and how we use the resources around us,” Mai said in an interview with Caribbean Journal.

Where Visitors Stay

Accommodation follows the same approach. “There are homestays available,” Mai says, “but most visitors stay at small lodges and resorts located in towns and villages.”

These are modest, locally owned properties, often near rivers or forest edges. Meals depend on what is available. Owners are present. Conversations stretch across the table. Staying here feels integrated into place rather than separate from it.

Why Visiting Matters

“Tourism already contributes to our communities,” Mai says. “Visitors support us by participating in activities and learning from our culture.”

That contribution stays local. Guests purchase handcrafted items made from palms and seeds. Community-managed Maya sites receive donations that help with maintenance and conservation.

“When visitors join a Maya living experience, they often buy the crafts we make,” Mai says. “That support helps our families directly.”

The district’s needs remain visible. “In the Toledo District, there are between 39 and 43 Maya communities,” Mai says. “Many of them still do not have access to electricity or basic infrastructure.”

Sometimes visitors give more. “I remember when I was a community leader,” he says. “Tourists learned about our needs and later helped us renovate community buildings and support schools with supplies.”

The exchange remains simple. Visitors arrive. They participate. They leave something meaningful behind.

Why Toledo Is Next

“We need more information out there about what Toledo has to offer,” Mai says. “The resources are already here.”

That information is beginning to circulate. Travelers are looking for places that remain intact and personal. Toledo fits that moment because it has not reshaped itself to chase attention.

Belize’s southern district has never been hidden.

It has simply been quiet.

Now, travelers are starting to notice.

Guy Britton

2026-02-11 22:58:00