For decades now, watch collectors have become enamored with the significance, popularity, and (perhaps most importantly) the absurd affordability of Soviet-era watches. There’s the ingenious Vostok Amphibia dive watch; the various Poljot and Strela chronographs vital to the Russian space program; and the minimalist, glossy-white Raketa Big Zero that signified “the end of history.”

What’s lesser known are the timepieces from another part of the Iron Curtain—East Germany, which once encompassed two of the most significant areas of the historic watch industry. Today we associate German watches with the town of Glashütte, where Walter Lange set up a watchmaking school in 1841 and evolved it into one of the great horological houses.

Meanwhile, about 300 kilometers to the west is the town of Ruhla. Like Glashütte, Ruhla was also known for metal mining and a tradition of blacksmithing and metalworking. After World War II, it also happened to fall into the Soviet occupation zone, even though it was as far west as one could get. Perhaps it was always fated for this.

Both sides faced the evolution of pocket watches to wristwatches, on opposite sides of the World Wars. After 1945, the watch factories in Glashütte and Ruhla were reorganized into publicly-owned enterprises—having endured reparations back to Moscow (to jump-start the USSR’s own watch industry) and the general devastation of the war. Glashütte was a more established watchmaking hub, resuming production by 1946. In 1952, Volkseigener Betrieb Uhrenkombinat Ruhla became a state-owned enterprise.

Simplicity was the focus here: the Caliber 24 movement was an exercise in horlogical minimalism, and in the words of one historical source, “materials for production could be sourced from within the German Democratic Republic or from other socialist nations to fit with the ideals of communism.”

That said, up to 60% of production went outside the borders of the GDR. The industry was booming, and Ruhla spearheaded the success: by the mid-1960s, it employed 8,000 people who were producing 5 million watches per year. Not only were most of the components produced in-house, but all the materials had to be sourced from behind the Iron Curtain. By 1967, the entire watch assembly process was almost entirely automated—a milestone in watch production that not only reduced steps by a third, but also could spit out a functioning movement in 30 minutes.

Ruhla produced instruments for aircraft like the Ilyushin Il-14, dashboard clocks and quartz timers that made their way into Trabant rally cars, and chess clocks for the perennial Cold War drama of international chess tournaments.

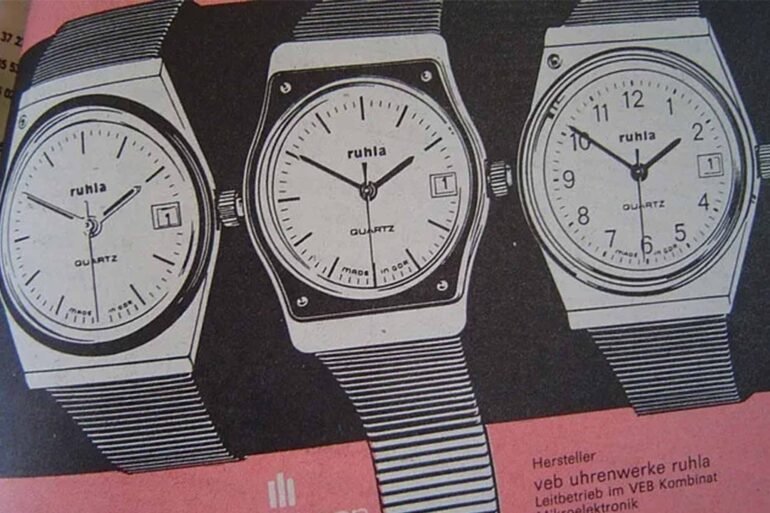

The watch designs themselves were a dizzying variation, all featured within the pages of Ruhla catalogs and distributed across Western nations. There were dive watches with “wasserdicht” and “stossgesichert” (waterproof, shock-resistant) markings, translucent plastic watches, funky television cases, and even designs that seemed to predict Swatch. The wackelaugen (“waggle eye”) watches for children are especially fun: depicting everything from cartoon cats to figures from German folklore, with eyes that move with the seconds.

Interkosmos, an international component of the Soviet space program with a delightfully futuristic name, aimed to rope in foreign nations to fly among its cosmonauts. Warsaw Pact countries were first in line, but the program spread around the world: it included the first non-Russian or non-American in space—Vladimír Remek, from Czechoslovakia—as well as the first Hispanic and Asian astronauts (hailing from Cuba and Vietnam, respectively). Even Western countries were involved: France, Australia, and the United Kingdom all sent crew members.

And for Sigmund Jähn, Interkosmos gave him the opportunity to represent both sides as the first German in space. As a child, Jähn had witnessed the Opel RAK rocket cars that captivated crowds in the late 1920s. A career in the East German Air Force prepared him to fly to Salyut 6 in 1978, an extension of the world’s first space station just seven years earlier.

Jähn carried four Ruhla watches, one for himself and the rest as gifts for his fellow cosmonauts. The watches were blocky with hidden lugs and integrated bracelets, the boon of sports watches today; Ruhla gave them commemorative dials in sunburst brown that featured the Interkosmos logo. They also had the first quartz movements produced in the Eastern Bloc—Ruhla having beaten the Soviets with Quarz 32768 as early as 1972.

After eight days Jähn returned safely to Earth, and held onto his watch until his death in 2019, the last living holder of the title Hero of the German Democratic Republic. The Ruhla brand was resurrected in 2023 with a replica of the first German watch in space, a fitting footnote to this oddball intersection of horology and space.

Blake Z. Rong

2025-12-26 15:00:00