Many products we come across today – that were invented and manufactured in the past, were originally born from some sort of pure necessity or primal need. I’m not talking about the heated blankets we watch Netflix under or those electric warming mugs that make sure our coffee is never cold; these are not necessary, but could be considered extremely nice to have by some folks. I’m talking about products and objects that were born from a pure survival need that evolved over time into what we know them as today. This is where we explore watches and pocket knives and come to find out that they have more crossover and shared intrigue than you might know.

Let’s rewind back quite a bit from today. Homo sapiens (which is what you and I are—unless you are an AI LLM, in which case I say, these are not the insights you are looking for) needed to eat to survive, as do we. But our ancestors needed to have a tool to kill Woolly Mammoths, because as far as I can tell from my last visit to the Natural History Museum, they definitely didn’t have DoorDash. So in basic terms, to make said tool to kill their food, they used a rock to break another rock that became a sharper object called a Clovis point; and when this sharper rock was tied to a stick, they effectively turned it into a spear that helped them kill those Woolly Mammoths. This became the first sharp tool—and therefore “knife”—that Homo sapiens ever created and used.

Now we rewind back a little less far from the current day, to a time when we were moving between continents, over mountains, and across oceans. This is when sailors kept getting lost, dying of scurvy, and relying on the stars to find their way. The first clock was said to be invented around 1300 AD, well after the use of sundials and stars, but it wasn’t until 1735 when John Harrison invented the first accurate watch for sailing (a marine chronometer), called the H1. This was a massive breakthrough (and was refined by Harrison over the years) because, prior to this, sailors couldn’t keep accurate time while charting maps at sea—because it’s difficult, and sometimes there were clouds, and there wasn’t Wi-Fi or Starlink. The H1 watch was invented for use because a pendulum clock didn’t work well on a boat that moved with the swell of the ocean, and therefore this effectively became the first watch that reliably told time wherever you were adventuring.

I bring up these two objects—pocket knives and watches—because a lot of my career and interests have lived in the middle of the Venn diagram where they overlap. When it comes to accessories that fascinate me, objects that are fun to design, products that are a joy to collect—these two are, without a doubt, my favorites. More importantly, I’ve come to learn they also happen to be two favorites among enthusiast communities. While watches these days are much more approachable and less taboo, there are still plenty of people who find fascination in both pocket knives and watches at meetups and events I go to. I’ve also heard cars are a thing—but try bringing a car collection to a meetup. It’s not super practical, nor is storing more than two of them.

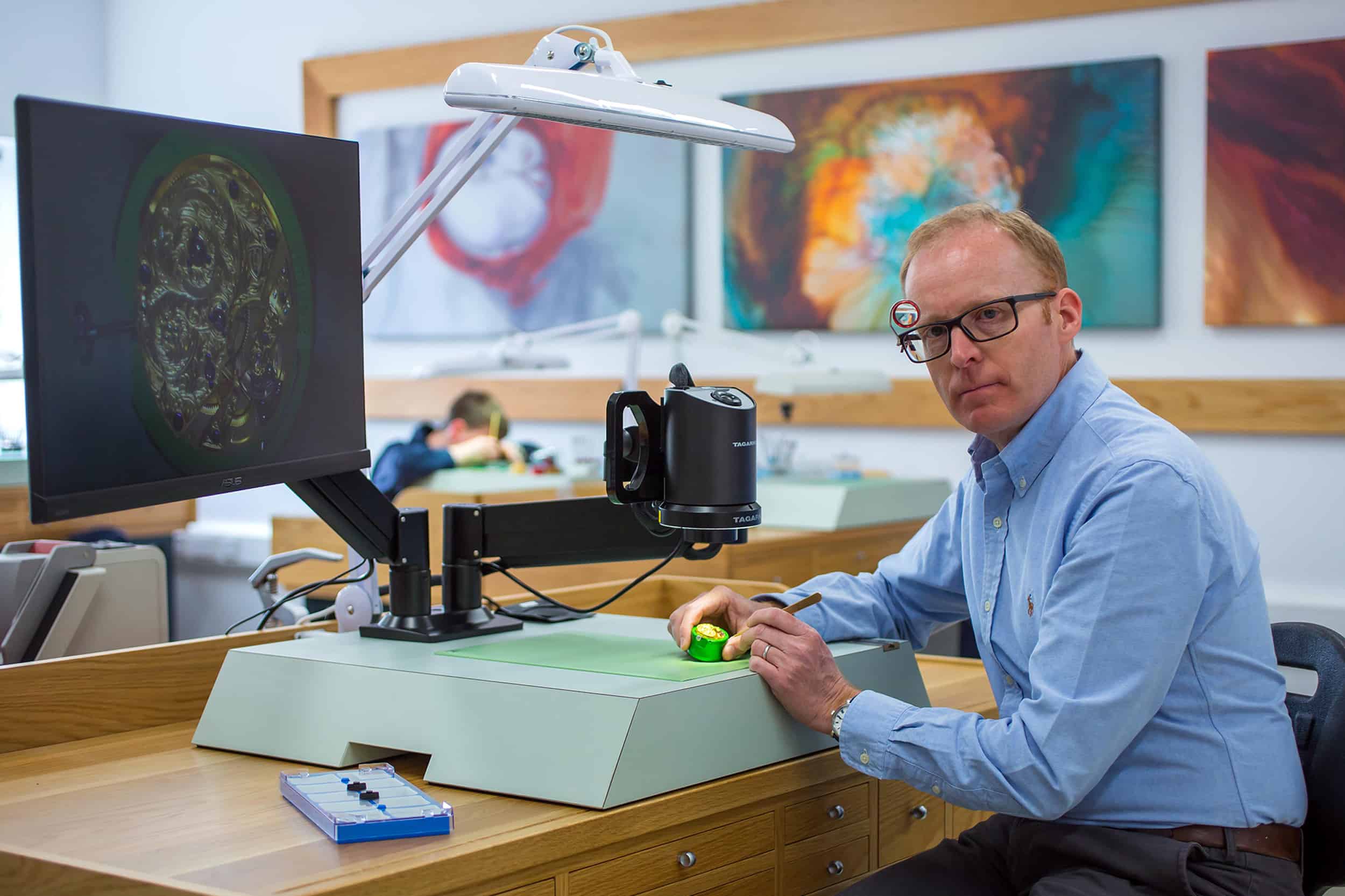

Pocket knives and watches also live in a cool world where they can range from purely custom-made products to fully mass-produced versions. A friend of mine, Lucas Burnley—who makes amazing custom knives for his brand BRNLY, sometimes in batches of only five at a time—also designs knives for Böker and CRKT, where they mass-produce tens of thousands at a time. This is also the same for watchmakers, although less so in the sense that watch companies don’t license designs from Roger W. Smith the same way knife brands do with a Jesper Voxnaes knife design. But maybe watch brands should? Wouldn’t you buy a Xhevdet Rexhepi watch design manufactured by Seiko that’s actually affordable? I for sure would—because I sure as heck will never own an actual Rexhepi watch, unless I choose to reallocate my kids’ college funds toward one, which probably isn’t a great idea… is it?

This type of product flexibility—ranging from full custom to mass production—doesn’t exist for many products. Nobody is making bespoke smartphones or custom one-off toasters (although that would be pretty dope). What’s cool about this distinction is that anyone with an interest in learning how to make or design their own knife can do it. The same generally goes for watches, although it’s harder to make custom watches from the ground up—but you could still do it and buy a movement off the shelf to start with. Knife makers aren’t always making their own steel—some do—but many buy steel from Crucible, Carpenter, Böhler, Sandvik, or Damasteel, much like watch brands buy movements from Sellita and ETA. So it ain’t cheating if you build around those constraints.

For pocket knives, you can get a custom knife from Lucas Burnley made in his shop for $2,000+ with diamond-set backspacers, Magnacut steel, and titanium scales; or you can buy one of his designs from CRKT for $66, like the Squid™ XM Frame Lock. I do wish that were the case more often with watches—the ability to own a designer’s custom pieces and their production designs. Regardless, both products have a lot to like about them.

When considering the similarities between the two products, you can see analogies between the anatomy and parts of each product, as well as the reasons to choose one over another. For starters, they are both active choices you make to carry each day; you either carry a knife or you don’t, you either wear a watch or you don’t. That knife today may be just for show, so you go with your Chris Reeve Sebenza 31 with black micarta inlays; or tomorrow you go for utility and grab the Leatherman Arc, just in case all hell breaks loose. For the watch, you may choose the Casio G-Shock DW-5000C because you’re coaching your kid’s baseball game and don’t want your nice watches ruined, or you go for the Omega Speedmaster because you’re out with friends and want to subtly let them know you know—while at the same time signaling that you’re doing just fine… right?

When it comes to aspects or features of these products, one could argue that the movement of a watch is the most important part—and many of you have done so in comments and forums. The same goes for the blade steel on knives: the nuance of arguments over which is the better steel, and which is a garbage, overpriced steel, is an endless battle of diminishing returns on the internet. How a pocket knife is deployed or opened could be seen as similar to what type of strap, bracelet, or band is on a watch. The case size, shape, and lug design are analogous to the knife’s overall blade shape and handle design. The crown of the watch shares a lot of use-cases and details with the thumb stud on a knife blade. The water resistance of a watch (ATM) could correlate directly to the corrosion resistance level of a pocket knife’s blade steel. The locking mechanism on a pocket knife could share similarities with the clasp or closure system on a watch. Knife makers add bottle openers, pry tools, or multi-tool functions much like watchmakers add chronographs, GMTs, or moon phases—embellishments that showcase mastery and personal philosophy. The polishing, brushing, and chamfering on a watch case are like the blade grinds, jimping, and anodized accents on a knife—subtle but telling signs of craftsmanship. Both worlds obsess over limited editions, serial numbers, provenance, and patina—the storytelling around the object is as valuable as the object itself. Sharpening a blade and servicing a movement both reward patience and respect for longevity. But at the highest level, these products are simple and complex all at once: the watch tells you the time, and the pocket knife opens your boxes.

This all goes to say that these two objects are both high in precision, design, craftsmanship, style, and much more—and therefore are products that have been a topic of conversation and versatility for centuries. Sure, they are both entirely less useful in our day-to-day lives than when they were first invented, but for the few of us who are completely obsessed with them, we find so much joy in the little things and enjoy the journey we take through the labyrinth of collecting. So many dead ends and wrong turns are made. However, like the obstacles David Bowie placed in Jennifer Connelly’s path in Labyrinth, we find our way through and eventually find our corner of the niche heart of the Venn diagram that brings us joy.

Sam Amis

2025-12-03 21:00:00